Turkey Hill’s Conestoga, Pa., plant transitions to renewable energy

Turkey Hill focuses on waste reduction as a way to both empower employees and become more sustainable

2019 is a big year for Turkey Hill Dairy’s Conestoga, Pa., plant: It’s the year it became one of the first major ice cream or ice tea facilities to be run on 100% renewable energy.

The plant achieved this lofty goal through a combination of power from wind turbines and its new relationship with Safe Harbor, a hydroelectric dam located just four miles from its plant, said John Cox, Turkey Hill’s president. Safe Harbor creates electricity using the Susquehanna River, which runs by the plant and will supply about 80% of Turkey Hill’s annual energy needs through local power sourcing and hydroelectric energy credits.

But Turkey Hill’s vision for sustainability goes beyond the typical ways companies conceive of “going green.” Cox said it’s all about waste reduction, which includes everything from recycling and figuring out what to do with wastewater to reducing wasted time in the production process.

“Sustainability really is a waste issue,” added Cox. “What are you wasting that consumers shouldn’t have to pay for? There’s a lot of business value in driving that waste out.”

From simple to complex flavors

Turkey Hill’s 244,159-square-foot plant is laid out over three floors — and not according to how one would walk through the production process — said Michelle Finch, senior operations manager. The ice cream-making process begins in the basement in receiving, where the company gets deliveries of dairy products, as well as bulk ingredients.

Building on Turkey Hill’s commitment to its local community (See Processor Profile, page 40), the company’s milk is mainly sourced from farms in the surrounding Lancaster County.

The company’s raw receiving area is in operation 24 hours a day, seven days a week, Finch noted. The plant has two bays, which means it can receive two tankers at once. Seven to 10 truckloads of milk and cream are delivered every day.

From receiving, the dairy products go into batching, which is when the ice cream mix is actually made. Turkey Hill has two blending systems that bring in raw materials from receiving to make either a white or a chocolate mix, Finch noted.

Turkey Hill has two rework tanks, which allows the plant to collect leftover mix from production runs. This mix can be re-pasteurized and used in future batches while keeping within quality standards. Finch said the tanks are a part of Turkey Hill’s philosophy of not wasting any materials.

After the ice cream is batched, it is pumped up to the third floor for pasteurization. The plant has four high temperature/short time systems for pasteurization, though not all are used for ice cream (the plant also processes iced tea and other drinks). According to Brian Naff, continuous improvement leader, this is one of the plant’s “critical control points” for the plant where testing is done to ensure food safety and quality product.

The next step is pumping the ice cream batches to the first floor for flavoring. Genise Wade, vice president of operations, said the production schedule is arranged to reduce allergen risk, “starting with more basic flavors and getting to more complicated ones before you have to stop and clean.”

Naff concurred.

“We’re really trying to build compatible allergen flavor sequences to build out 72-hour production schedule windows in between cleaning events.”

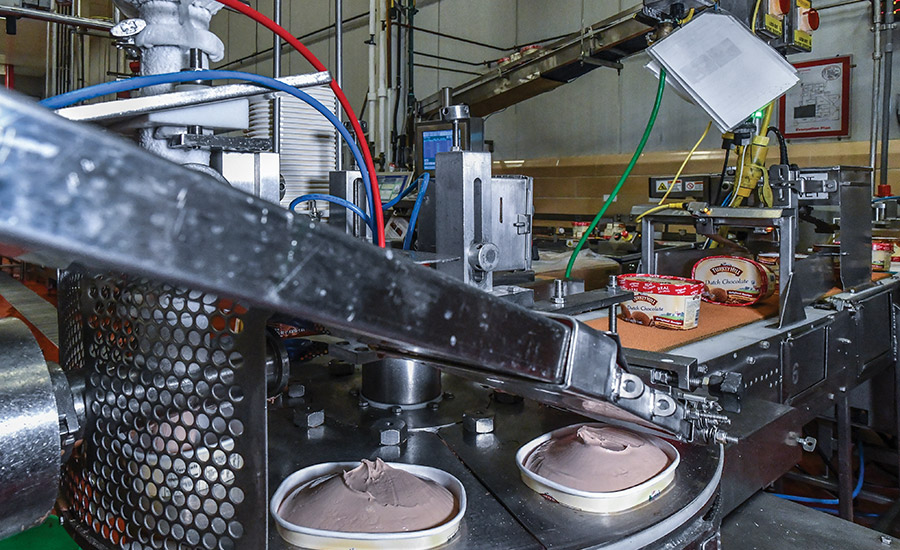

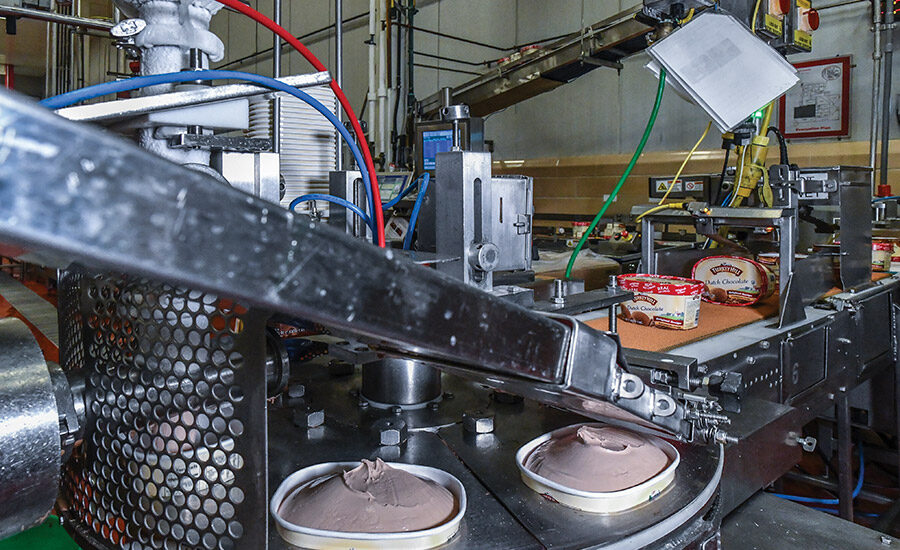

In the ice cream production room, there are 12 500-gallon and four 250-gallon flavor vats. Finch said that the plant’s “associates,” which is what Turkey Hill calls its employees, pull in either a chocolate or white mix and add flavors for the product they are running. The product then goes through its first freezing, at which point it has the consistency of soft-serve ice cream. After the initial freezing, variegates and inclusions are added. One of the fillers also has a blender in it, which is used to blend “liquid chip” with ice cream to make chocolate chips.

“We add all the good stuff after we freeze it,” Finch added.

The ice cream is then filled into 1.5-quart containers by the plant’s five fillers and the lid is immediately put on. Then every other container is flipped by a machine so the containers can be nestled properly in the wrapper, Finch noted.

After filling, the containers go through metal detection and are put into six-packs to go into the hardener, which is set at -40 degrees Fahrenheit. The containers travel down a belt from the hardener to the palletizer. After they are palletized, they are put into the plant’s 79,000-square-foot storage freezer, which is set at -20 degrees Fahrenheit. Finch said the freezer holds four weeks’ worth of inventory at any given time.

She said this is the end of ice cream’s journey at the Turkey Hill plant: The containers go out for delivery from the freezer.

And starting this year, the entire ice cream production process is accomplished using only renewable energy.

Green history

Cox said that Turkey Hill was interested in running a sustainable plant before it was the topic du jour. Back in the 1990s, the plant began packaging milk in plastic jugs instead of paperboard cartons, but it was concerned about the environmental impact of its new packaging. So it launched its own recycling program. Customers could bring in used jugs to the store, and Turkey Hill would recycle them at its plant.

“It cost us a lot of money,” Cox said. “I don’t know that it actually gained us any sales because I don’t know at the time consumers cared one whit about whether it was green or not.”

Since then, the company has invested in many green initiatives both within its Lancaster County, Pa., community and in its own plant (see Processor Profile).

Cox said that in 2006, Turkey Hill partnered with a local solid waste management company and public utility to participate in a landfill gas-to-energy plant project. The “green plant” generates electricity with biogas from operations. Turkey Hill sends water to the green plant where the waste heat from the generator is used to make steam, which is piped back to the plant.

“We replaced diesel in our boilers with the steam that we were getting from that,” Cox said. “That saved us … around 150,000 gallons of diesel a year.”

One of the next “green” steps the company took was operating its own wastewater plant, Cox said. To make this treatment plant more sustainable, the dairy completed an alternative fuel boiler project, allowing Turkey Hill to substantially replace its use of propane fuel with biogas generated from the plant’s digester.

Another important moment in the plant’s sustainability journey was entering into a relationship with the Susquehanna River Basin Commission to manage the amount of groundwater it takes from the local aquifer, Cox said. Through this relationship, Turkey Hill developed a sustainable groundwater management program where it isn’t depleting the local aquifer at all.

‘Waste-management’ technology

Turkey Hill’s waste-reduction philosophy, in terms of employee productivity, is similar to how the company approaches production. For example, Turkey Hill began training all of its plant associates in LEAN management principles, which help eliminate non-value-adding activities and wasted time, 11 years ago, Cox said. The idea behind LEAN was to build associates’ teamwork skills and help them identify areas of waste in their day-to-day work.

Another way the company looks to reduce wasted time is by adding in new technology to help associates do their jobs better, Naff said.

“A lot of the technology we focus on is around automation,” he said. “It’s really taking manual work from our associates’ hands and giving them a tool to use to reduce wasting their day.”

In addition to automation, Naff said Turkey Hill uses tablets to augment associates’ work; the associates use them to monitor real-time line performance and equipment downtime.

Cox said it’s important to note that technology is mostly used at Turkey Hill to enhance associates’ work, not to eliminate jobs.

“It’s not that we’d never replace human effort or work or thinking with technology,” he said. “We do sometimes, but our primary strategy is to use technology to help people work better and smarter.”

Structure of empowerment

Turkey Hill’s philosophy around technology corresponds to its philosophy around work structure: finding the best way to empower its associates to be more engaged.

Four years ago, Turkey Hill completely upended its hierarchal structure to “walk the talk,” Wade said. To change its work structure, it asked for the input from its hourly associates. Some of them volunteered to help design the new system. Once it was in place, these volunteers were advocates for the new structure and helped explain it to their coworkers.

The current system involves different levels of technical and leadership skills, Finch noted. It also involves much more cross-training on equipment. In the past, there were fewer opportunities to move up because the associates had more limited expertise. Now they can pick up new skills along the way in order to get promoted.

“There are the types of activities, tasks and competency demonstrations that we want to see out of our associates,” she added. “So they have to demonstrate them, and they have training champions that help them go through those skill blocks.”

When associates first start, they are at a level called “new hire.” In the first six months, they move to the General Utility level, wherein they are expected to know how to operate one piece of equipment. From there, the associates move to the Tech 1 level. This is the level that all associates are expected to be at within one year, Finch noted.

At Tech 1, associates know how to operate and troubleshoot multiple pieces of equipment. But it’s not just about technical skills, Cox said.

“You have to be able to be a good team member at Tech 1, which includes being able to talk to other people, take feedback and give feedback,” he said. “You [have to] participate on the team in a meaningful way.”

Tech 2 is the next level. At this stage, associates are in leadership positions and have higher-level technical and mechanical skills. Wade said they have a few people at the Tech 2 level right now. The next planned levels are Tech 3 and Tech 4, but Turkey Hill is still discussing what these promotions will look like. It wants to create multiple paths for advancement.

“So if I’m not mechanically inclined, can I also find another path to get to there?” she said. “You might be specialized in a certain area of safety, or quality or reliability. We’re working on those, and that’s the plan for ‘19 to have those established.”

Audit-ready

Besides being empowered in their own work, associates are empowered to keep the Turkey Hill plant “audit-ready,” meaning they are always prepared for any food safety or sanitation audits. Finch said the work structure allows more ownership over cleanliness: The associates are responsible for both operating and cleaning their machines.

In addition to being SQF-certified and following Food Safety Modernization Act standards, the plant has its own system for keeping everything sanitary. Wade said when she first started working at Turkey Hill, she was struck by how clean the plant was.

“Everyone has a personal responsibility to help keep our plant clean in their work areas, as well as support our other departments,” Wade said. “So it’s a team effort … and if somebody else needs a little help, you go and help in that area to make sure that we’re doing it right.”

Part of the plant’s audit-ready motto is its “stop and fix” policy, said Tom Weber, continuous improvement leader. This means that if associates know they aren’t passing along a perfect product, they should stop what they are doing and figure out a solution.

“When everybody in the organization, no matter where you work, does that, it guarantees product quality to your customers,” he added.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!