What’s the impact of Avian flu on dairy farms?

H5N1 influenza strain found in 190 dairy herds in 14 states, vaccines in cattle authorized.

Cows infected with bird flu range in symptoms, and while consumption of pasteurized milk products should be a low risk, Seema Lakdawala, Ph.D., and the team at Emory University suggest that farmers, dairy processors, and scientists work together on solutions.

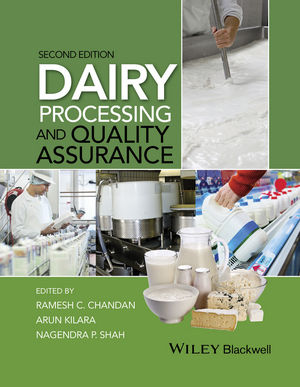

Photo courtesy of the Center for Dairy Research.

Sanitation on dairy farms and in dairy plants is a top priority with heat exchangers ensuring that raw milk is properly pasteurized and safe for human consumption without bacteria like E coli and salmonella. Lately, though, there’s been an outbreak of a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAI or H5N1), jumping from cow to cow, from cattle to cat, and even a racoon, per the researchers at Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y.

Highly pathogenic H5N1 viruses from this current outbreak were first detected in 2022 in migratory birds, while the first reports of dairy cattle with an unusual illness occurred in February and March 2024, notes Seema Lakdawala, Ph.D., associate professor at Emory University’s Department of Microbiology and Immunology in Atlanta, Ga.

“So far there have been 14 human cases in the U.S. from exposure to infected cattle or poultry,” she says. “So far cases are mild, however H5N1 viruses are known to be lethal in humans and has previously reported to have a 30% mortality rate.”

John Lucey, Ph.D., director of the Center for Dairy Research (CDR) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, concurs that while symptoms for humans have been relatively mild, “federal agencies are recommending dairy farm workers that have close contact with cattle use some type of protective clothing especially items like face shields while milking,” he says,

He also stresses that all equipment that comes into contact with milk should be cleaned and regularly sanitized at both farms and dairy plants. “This helps to prevent raw milk from being contaminated with pathogens, for example, if the cow was sick or if the outside of the udder/teat was not cleaned before milking,” Lucey explains.

According to the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), as of May 2, 2024, 36 herds have been infected in nine states, and testing found that 1 in 5 retail milk samples analyzed were positive by polymerase chain reaction for the H5N1 influenza strain, which is highly pathogenic for birds. Milk that was pasteurized, however, did not contain live influenza virus and is, therefore, considered to be safe.

As of late August, the number of infected cows and states impacted is growing. According to Lucey and Lakdawala, between 170 and 190 dairy herds in 14 states, most recently California in addition to TX, NM, OK, KS, CO, WY, ID, WV, SD, MN, IA, MI, OH and NC, have tested positive for H5N1. For the latest numbers, visit the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/situation-summary/index.html

Role of milking machines in bird flu

When asked about the role of milking machines in bird flu and whether that could lower milk supply due to infected cows — which would have a huge impact on staple dairy foods like cheese, ice cream and yogurt since fresh milk is a key ingredient — Lakdawala tells Dairy Foods that cow’s milk contains plenty of H5N1 infection, “on the range of thousands to millions of infectious viral particles in 1 milliliter of milk.”

Additionally, cows infected with the virus range in symptoms, and the changes in milk consistency may not be immediately observed in the milk of an infected cow.

“Thus, when an asymptomatic or symptomatic infected cow is milked, residual milk on the claw could infect the cow that is milked after that cow,” she explains. “Research from my group has demonstrated that influenza viruses are highly stable on milking equipment in milk and may be a source of spread for the virus to other cattle and dairy farm workers.

The number of cows infected with the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAI or H5N1) is increasing, but pasteurization of milk and proper sanitation can prevent spread.

Photo courtesy of the Center for Dairy Research.

“The lower milk supply is likely due to the virus replicating in mammary cells in the cow and that is impacting the production of milk also, this is how the virus is getting in the milk,” she adds.

CDR’s Lucey, on the other hand, doesn’t see a large impact on milk supply. He suggests that while infected cows show a large reduction in milk while they are sick, most recover within a few weeks and milk production seems to “mostly recover too.”

Although the testing of retail milk just detects residual genetic material, pasteurization of infected milk kills the virus, with follow-up testing of milk samples not showing any active virus, Lucey adds.

Yet, there is an incubation period. Just like in the case of COVID-19 in humans, cows can have virus a week or 10 days before they show symptoms that they are sick. “Infected cows have high virus numbers (load) in their milk,” Lucey explains.

Lakdawala’s research team at Emory University focuses on the spread of influenza viruses, typically exploring how it spreads through the air.

“We focus on understanding the prevalence of viruses in the air and on surfaces to explore ways to reduce the spread of influenza viruses using environmental and/or pharmaceutical interventions,” she says. One research article, “Influenza H5N1 and H1N1 viruses remain infectious in unpasteurized milk on milking machinery surfaces” is available here.

Safeguards and prevention

To prevent the spread, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), CDC, and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have been doing regular briefings and updates for the public and stakeholders. The three federal agencies also have specific websites with the latest findings and recommendations.

In addition to regular communication, Lakdawala advises that there should be more emphasis on identifying individual cows with H5 virus in their milk, so they can be isolated. Other safeguards should include enhanced precaution by dairy milkers and stringent disinfection of equipment.

“Vaccination is a future possibility, but I do not think is actively being considered at this time,” Lucey says, noting that testing continues to be done at National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN)

Yet, vaccines are indeed moving forward. On September 4, USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack announced at the Farm Progress Show in Boone, Iowa, that he has authorized the first field trial of an H5N1 vaccine in cattle, to be overseen by the USDA's Center for Veterinary Biologics (CVB) in Ames, Iowa.

Lakdawala concludes: “Consumption of pasteurized milk products should be a low risk, but we should all be concerned with the scope of the current outbreak. No one wants another pandemic and in dairy cows, H5N1 is taking billions of shots to enter humans and be successful within humans. We need to do whatever we all can to protect the workers and veterinarians on dairy farms and reduce the spread of the virus between cattle.”

Think you know everything about the impact of Avian flu on dairy farms? Put your knowledge to the test! Take our quick quiz and see how you stack up. Challenge yourself, share your results, and learn something new – all in just a few minutes!

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!