Solutions to common challenges with 640-pound cheese blocks and barrels

Large block cheese sizes struggle with moisture migration.

Photo courtesy of ChiccoDodiFC / iStock / Getty Images Plus

John A. Lucey is a professor of food science at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and the director of the Center for Dairy Research.

In the 1970s, some companies began producing cheese in large 640-pound blocks to reduce handling and packaging costs. Before then, the largest format that cheese companies were routinely producing were 40-pound blocks, but when these are sent to the converter, they require manual handling to remove the packaging from each of the blocks and have more trim losses when converted into exact weight retail chunks or bars. Yet, 640s provide a more economical and efficient solution for manufacturers and converters.

Today, 640s are still widely produced and utilized in the dairy industry and while they have their advantages, they also pose challenges. These challenges include variable moisture levels throughout the block of cheese, which results in inconsistent texture and flavor development throughout the block or barrel. Other potential issues include poor curd knit, mold on surface, and gas defects. Barrels are another common large format utilized for cheese. Many of the same challenges and solutions apply to barrels as well.

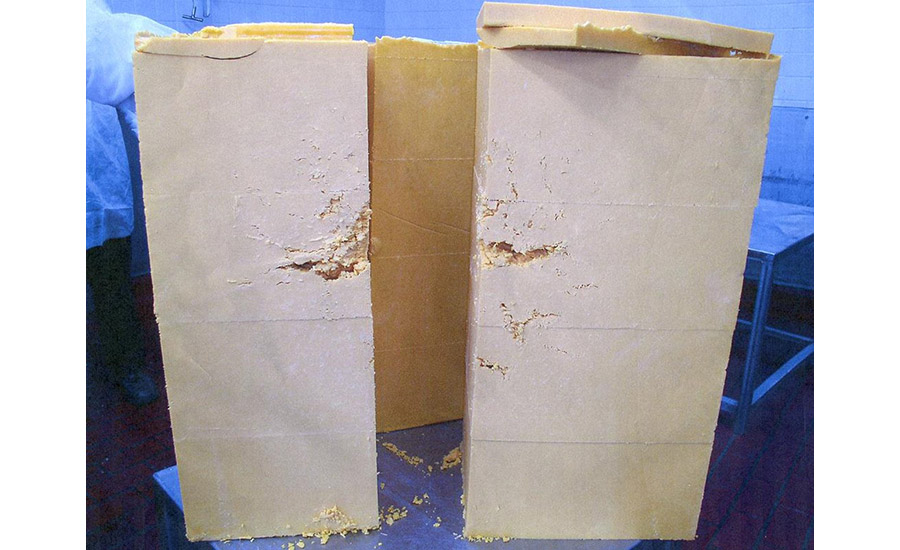

Perhaps the biggest issue in 640s and barrels is moisture migration. 640s can have as much as a 5% difference in moisture between the exterior and the interior. Although, some companies can successfully reduce that variability to within 1% of a moisture range. Lower moisture levels are usually observed in the interior and higher levels near the outside. Moisture migration is driven by different rates of cooling within the block. The core stays warmer longer and the outside cools faster. Colder curd is better at absorbing moisture than warm curd (which can expel moisture or serum from the matrix).

To mitigate this issue, cheesemakers should try to remove as much of the free whey (serum) from the block as possible before it is sealed. Free serum is still being produced after salting when the curds are still warm. It is difficult to get all the free whey out of the block because it’s a long distance from the core to the outside. Strategies used to remove much of the free whey from the block include use of V-shaped screens or vacuum powered probes, which are lowered into the 640 or barrel to allow more free whey to be removed.

Another strategy is a process called collating. In this process, 16 40-pound blocks are pre-pressed and then either manually or mechanically fed into a 640-pound box. Because it is easier to remove whey from a pressed 40-pound block than a 640-pound block, collated 640s typically have less free moisture to move about within the block. Thus, collated 640s have a lot less moisture variability than the standard 640s.

Rate of cooling (or large temperature gradients between the inner and outer portions of the blocks) also plays a key role in moisture migration. The faster the block is cooled, the bigger the temperature differential will be between the core and exterior, therefore the more moisture migration will occur. But if the block is cooled too slowly, manufacturers run the risk of excessive acid development.

Another issue could be gas formation in the warm interior of the block, if the curd is contaminated with a heterofermentative gas forming bacteria, which results in gas holes and pockets. Dean Sommer, cheese and food technologist at the Center for Dairy Research (CDR), recommends that manufacturers should aim to get the core of the 640 cooled down to 45 degrees Fahrenheit in less than 10 days.

Another issue with large block/barrels is poor curd knit due to entrapped air (or occasionally caused by a lack of acid or curd that was too cold during pressing). Cheeses like Cheddar produced in 640s can end up with poor curd knit and look more like an open bodied cheese like Colby. It can be a challenge to get most of the entrapped air out of the very large block. The solution is slightly counterintuitive. Most people would think the solution would be to put pressure on the cheese as soon as it is in the box to push the air out. In fact, the solution is to let the curd naturally settle in the box/barrel after it is filled and some of the entrapped air will be escape before the 640 is pressed. If the cheese is pressed immediately, the cheese surface will essentially close up, and the air can’t easily escape. Manufacturers put the cheese through a vacuum chamber to pull more air out of the cheese, which also helps with better knitting of the curd.

Mold growth during storage and aging is also another common issue with 640s. Part of the reason is that 640 packaging is not a vacuum sealed bag. It is wrapped in plastic within the plastic or wooden form, but it is not normally vacuum sealed. There are a couple of strategies to deter mold growth on the surface of the 640. Good sanitation practices in the plant as well as proper air flow (and filtration) and handling can help prevent mold formation.

When sealing the 640, plants can apply an antimycotic like natamycin to the top and bottom surfaces where mold growth is most likely to occur. Another solution, which a few plants still do, is apply some hot paraffin wax around the inside of the 640 box and then, when the top and bottom boards are put on it, the wax helps form a better seal.

The CDR has explored approaches to help improve the quality of these 640 blocks. This includes standardizing the lactose content in the milk, i.e., reducing it to the level required to attain the target pH, so that even if the cheese remains warm (slow to cool) there is no further lactose that can be fermented, thus lessening the risk of excessive acidity in some locations of the 640 block, which can be problem for some manufacturers. The pH of salting might also play a role as lower pH values allows the caseins to better hold onto the serum (due to greater loss of calcium), which might limit migration within the block.

Producing large-format cheese is a complicated process. Every dairy plant needs to fine-tune its procedures to find a process that results in high-quality 640s and barrels.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!