It’s all in the data at Oregon Ice Cream Co.’s plant

Oregon Ice Cream Co.’s software investments allow the company to make continuous improvements to its plant operations.

Beautiful Eugene, Ore., is tucked into the Willamette Valley — an area celebrated for its 500-plus wineries. Wine lovers from around the world flock to the region to sample renowned Pinot Noir and Pinot Gris varietals.

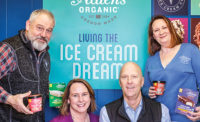

But the funky college town has another flavorful claim to fame. It is home to Oregon Ice Cream Co.’s 80,000-square-foot plant, which produces ice cream under the Alden’s Organic brand: the No. 1-selling organic ice cream brand in the natural channel in the United States.

The plant’s been in the ice cream business for years, first opening its doors in 1938 to produce Dutch Girl Ice Cream, says Charles Nutter, senior vice president of operations. Now, it produces Alden’s Organic’s 46 SKUs (see Processor Profile), which include ice cream pints and sqrounds, frozen novelties and dairy-free frozen desserts.

Key to the plant’s success is Oregon Ice Cream’s data-driven approach to everything from batching ingredients to tracking efficiencies to ensuring food safety. This approach allows the company to make smart real-time decisions to continuously improve its plant operations.

“Our relentless focus is ‘how do we get better every day?’” says Nutter. “So we are engaged heavily in data. We’re data geeks.”

It starts with organic cream

Alden’s Organic ice cream production begins when tankers deliver fresh cream from organic farms from the surrounding area, notes Nutter. The company sources from farms that have small herds and allow their cows above-average access to pasture.

Tankers take two hours to unload and one hour to clean before they are sent on their way, Nutter explains. The cream, along with other ingredients, is managed through the upstairs sourcing team. Here, plant employees receive daily enterprise resource planning (ERP) tickets that tell them which materials need to be sent down to the production staging area. The materials vary, depending on the day’s production schedule.

Oregon Ice Cream plans production schedules three months in advance to determine the quantity and type of ingredients they need to order. That’s why during some weeks, the plant receives three tankers of cream, Nutter says, but sometimes it will receive only one — for example, when it’s mainly producing frozen novelties (which require less cream) or dairy-free frozen desserts.

Once it is ready to be transformed into ice cream, the cream goes into the batching process, during which it is fed into one of two high-temperature/short-time (HTST) units. From there, the cream moves into one of five production lines, Nutter says. The plant’s production lines include three novelty lines (including one new state-of-the-art high-speed production line), an institutional tub line and a line that exclusively produces pints/sqrounds.

According to Eric Eddings, president and CEO, there’s an opportunity to use one of the original novelty lines to test production of new products created by the research and development (R&D) team. If the R&D line trials are successful, the company could then scale up production on the high-speed line.

Then comes flavor creation

On the day of Dairy Foods’ visit, the plant was producing Strawberry Sammies (round ice cream sandwiches) on the non-high-speed novelty line, Freckled Strawberry yogurt bars on the high-speed line and French Vanilla ice cream sqrounds on another line. According to Nutter, the plant normally keeps the same product running on a given line for the whole day.

After going through the HTST systems for pasteurization, the product moves into one of 10 pasteurized tanks, Nutter explains. This is the point when the base flavor is added in the plant’s 15 flavor vats.

On the line producing Strawberry Sammies, the flavored product then travels through an ice cream freezer, where blades turn it into ice cream. Afterward, the ice cream goes through an extrusion head. Variegates (such as organic strawberry) are added at this point through a spinner, which swirls them into the ice cream. In this case, the resulting product is cut by a heated wire to the appropriate novelty size and then sandwiched between two cookies.

The ice cream sandwiches then go into a freezer set at -45 degrees Fahrenheit, and move around the freezer on conveyors for 20 minutes. They come out “hard as a rock,” explains Eddings. The plant’s fast-freezing process is key to the finished products’ quality.

The frozen sandwiches are now ready to be packaged. They travel through a conveyor to be individually wrapped, Eddings says. After going through a metal detector and a checkweigher, they are put in larger boxes, which travel up a ramp to be palletized.

Automated line

A similar production process is followed on the plant’s other lines, but with much more automation on the high-speed novelty line. Oregon Ice Cream eventually hopes to upgrade its other lines to increase efficiencies, says Eddings.

The main difference on the high-speed line is that two extrusion heads are used, says Nutter. The line also features robots from Denmark, Italy, France and Germany.

“We’ve got the U.N. of equipment in here,” jokes Nutter.

To develop its high-speed line, Oregon Ice Cream toured other ice cream plants to see what kind of automated equipment they were using, Nutter says, and also worked directly with equipment suppliers to learn which robots would work best. The line was installed and brought on line in 2018.

Nutter says his favorite piece of equipment is the Dienst carton Machine, manufactured in Germany, which does most of the packaging process for novelties on the high-speed line. The robot picks up novelties, places them into a bucket of four, pushes them into a box and closes the flap. It then seals the boxes by injecting them with glue. He describes the machine as “the best he’s used in 30 years in plants.”

The sqround/pint line operates similarly to the other non-high-speed lines, but the ice cream undergoes a different freezing process. The pints/sqrounds go into a huge spiral freezer. They move by conveyor around the freezer, eventually traveling two stories up during the hour-long freezing process. The spiral freezer was installed in 2019, explains Nutter.

Data tracking

One way Oregon Ice Cream ensures the quality of its products is by its numerous testing points throughout production. This process is managed by the plant’s proprietary real-time data management system, which is an overall equipment effectiveness (OEE) cloud-based system that tracks machine availability, performance and quality, among other functions, explains Nutter.

According to Amber Everly, vice president of quality assurance and technical services, plant employees use the data management system on their tablets during production. They’ll get a notification if they need to do a quality check, and will take a photo of the product, its code date, its inclusions, the packaging or other elements, depending on what is needed at that checkpoint.

“Capturing the visual photo has been really helpful to go back and troubleshoot concerns or consumer questions,” says Everly.

According to Nutter, the data management system has also brought about a positive cultural change in the plant. It gives plant employees more ownership over the production process.

“It was about changing the culture, giving our folks an opportunity to have some tools to help them stay engaged,” he says. “And the thing about the system is it’s real-time, so they’re constantly looking at it.”

Oregon Ice Cream has other software tools along with the data management system to measure every aspect of the business. For example, it uses a Microsoft tool called Power BI that reaches into the company’s ERP system to produce daily dashboard reports.

“So we’re tracking efficiencies. We’re tracking waste. We’re tracking yields. We’re tracking downtime. We’re tracking downtime categories,” says Nutter. “We go in and meet about those every day to find out how we can improve.”

Employee incentives

The culture change at Oregon Ice Cream has another benefit: a lack of turnover, notes Nutter.

“In a town that’s got 10 food manufacturing companies, it says something I think about how we treat our folks,” he adds.

The company also uses software to give employees ways to learn new skills and to move up the plant’s hierarchy. One tool is called Alchemy, which “is a training regimen specifically for the food industry,” Nutter explains. Plant employees go through monthly trainings through the software. It also offers a Coach module, in which trainers observe plant employees’ knowledge of standard operating procedures.

“The beauty of Coach is that you can do observations. So within Coach, the person who’s doing the observation has questions of the steps within that procedure, and the observer will watch the employee doing that job,” Everly says.

This module allows Oregon Ice Cream to determine whether or not there have been any gaps in its trainings, notes Nutter, and make changes going forward.

Once employees complete training modules on Alchemy, they’re eligible to apply for higher-level plant positions. Eddings says that Oregon Ice Cream aims to be progressive from both a skills standpoint and a wage standpoint.

“If [employees] test and pass through these next levels of skill, they can then apply for the next level of position, and then they can actually be compensated for it,” Eddings adds.

Another incentive are bonuses given out at the company’s “town hall” meetings. Once a quarter, all the lines are shut down and employees meet to discuss progress on each team’s “scorecard,” or set of goals on which they are currently focusing.

“Depending on how well the team collectively has done on those goals, they’ll walk out of there with a fun bonus check,” says Eddings.

The scorecard system goes all the way up to the CEO level, and enables the company to track its progress on goal areas. Upper management’s goals trickle down into the rest of the employees.

“[It] will start with my scorecard, and it will cascade down through the entire organization, ultimately including the people at the plant that are coming to our town halls,” says Eddings. “We want to make sure that we’ve really got common ground on what matters most.”

Focus on food safety

Oregon Ice Cream has a “very robust” environmental monitoring system in its plant to ensure a high level of food safety, Everly says. After the day’s two production shifts have ended, some plant employees come in for an overnight sanitation shift. The sanitation has to be verified before any production employees are allowed onto the floor the next morning.

“Once the cleaning is done, the lab will come in, and they do ATP swabbing on the line, as well as [an] allergen rinse and water testing to verify cleanliness,” explains Everly. “And the lab, they’ll do a visual check. Once all the checks performed are passed, the lab techs will release the line for production.”

Additionally, Oregon Ice Cream performs weekly, monthly and quarterly pathogen swabs, depending on risk. If anything comes up as a hot spot, the company shuts down that line, deep cleans it and retests in triplicate to ensure products are as safely produced as possible.

Before a product can be released to retailers, the plant uses the Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point system. Products have to go through 10 to 15 checks prior to their release.

“It includes micro testing. It includes pathogen testing, metal detection, weight checks [and] a system of critical quality checks to ensure the product is meeting the quality standards,” Everly says.

It might take three to five days to get back the results of all the tests, which are done throughout the whole production process, Nutter notes.

“We’re testing at every point of the operation, including after HTST in the pasteurized tanks, and then off the line throughout the day,” he adds. “So, those tests then get sent in, or we do some of them ourselves, but we will not release the product until all those come back within specification.”

The data management system comes into play here, too. If an on-site lab employee notices that there is something awry, he or she can communicate immediately with operations to make changes.

“All those [software tools] are just so real-time,” says Eddings. “It changes the way our business is run.”

Photos by Nick Grier

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!