Dairy operations

Cleaning pumps and valves

Pumps and valves need to be cleaned thoroughly to eliminate allergens. Temperature, pressure, velocity and cleaning solution are some of the parameters to follow.

Pumps and valves move raw and pasteurized dairy products throughout a processing plant. As part of Dairy Foods’ focus on food safety this month, we asked equipment suppliers to share best practices in cleaning pumps and valves. Here is what they had to say.

Pumps and valves move raw and pasteurized dairy products throughout a processing plant. As part of Dairy Foods’ focus on food safety this month, we asked equipment suppliers to share best practices in cleaning pumps and valves. Here is what they had to say.

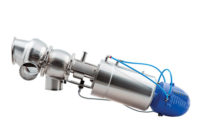

It is important that valves be designed in such a way that they are fully cleanable during cleaning-in-place (CIP), said President Dave Medlar of GEA Tuchenhagen, Portland, Maine. Generally, this means that valves should be designed with no deadlegs, pockets, sumps or domes which result in hard-to-clean areas within the valve.

It is also necessary to implement a CIP regimen based on a combination of time, temperature, velocity and the chemical composition of the CIP liquid in order to ensure proper cleaning, Medlar said.

Valves that are well-designed for ease of cleaning use fitted V-ring seat gasket technology, rather than O-rings. O-rings tend to roll in their grooves during valve operation, often allowing product in behind them, in turn making the valve very hard-to-clean during CIP, he said.

Each food processing application is different, according to SPX Flow Technology, Delavan, Wis. The parameters (temperature, pressure, velocity, cleaning solution, etc.) to clean pumps and valves vary and should be optimized until the process equipment is demonstrated to be cleaned.

For example, adequate cleaning solution pressure is necessary for proper cleaning of the valve. For valves, a CIP pump should be energized during cleaning especially when the valve is pulsing. Actuate the valve multiple times to clean masked seat surfaces and create turbulence in the line, said Chris Sinutko, a product and aftermarket sales specialist.

He said processors need to initiate CIP or a flush run as soon after a production run as possible to avoid drying of product in the line. Run CIP long enough and with the appropriate cycles (initial rinse, caustic, acid wash, final rinse, etc.) to clean the equipment. For valves, allow enough duration for seat pulsing to actuate the valve to full stroke.

Only the combination of well-designed components and optimized CIP parameters gives optimum cleaning results, said Product Manager Pascal Bär of GEA Aseptomag, Portland, Maine.

When it comes to aseptic processing in particular, “we recommend using valves with a minimal number of product contact seals and that these seals be only static in design.”

Every seal is a possible source of contamination and if the seal is dynamic, it is even more difficult to clean compared to static seals, he said. In addition, aseptic components need to be designed according to the latest hygienic standards. Bellow technology for valve stems minimizes the number of seals in contact with the product and maximizes the overall hygienic design of the valve, he said.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!